Theory - Gyroscopes

Consider a precessing Gyroscope that is just about to touch the floor. (The diagram above is a bird's-eye view of this).

If we use the formula linking arc length, radius and angle subtended, we find: $ Arc$ $length$ = $Radius$ * $Angle$ $subtended$

Then, at constant radius, for very small amplitudes: $ d(Arc$ $length) $ = $ Radius $ * $ d(Angle$ $subtended)$ so we obtain

$$ \frac{\dot{L}(t)}{L}= \dot{\theta(t)} $$Noticing that $\dot{L}(t) = Rmg$, $L = Iw$, and $\dot{\theta(t)} = \omega_{precession}$, we get:

$$ \omega_{precession} = \frac{Rmg}{Iw} $$ (Note: Precession means rotation about the z axis, not the gyroscope's own axis.)From this formula, we can see that the larger the moment of inertia of the flywheel about the rod passing through it ($I$), at constant mass ($m$), the slower the rate of precession. Notice that when the wheel rotation decreases due to frictional forces, the $\omega$ in the denominator decreases, which increases the rate of precession.

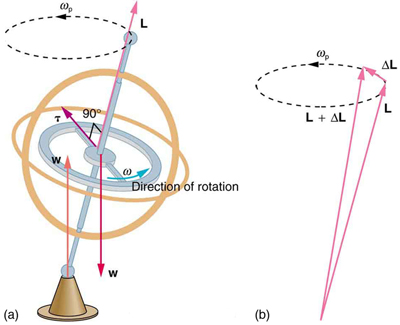

The torque experienced by the gyroscope is in a direction perpendicular to it's angular momentum about it's own rotation axis (which is about the rod passing through the flywheel). This means the change in angular momentum, in the same direction as the torque, is also perpendicular to it's own axis (recall that torque is the rate of change of angular momentum). As a result the angular momentum vector of the gyroscope begins to "follow" the torque; so the gyroscope itself begins to move around in a circle about the z axis, as the torque is always perpendicular to the angular momentum.

(linked from https://philschatz.com/physics-book/contents/m42184.html)

When the gyroscope wheel begins to slow down due to friction, so that $\omega$ decreases, the angular momentum of the gyroscope ($I\omega$) decreases. The torque ($R \times mg$), however, remains unchanged (at the same angle to the vertical) so the change in angular momentum due to the torque is larger in comparison to the angular momentum due to the wheel rotation ($I\omega$). As a result, the gyroscope "follows" the torque at a faster rate, as the torque is the rate of change of angular momentum.

Initially, when the gyroscope begins to fall down, it loses some gravitational potential energy which supplies kinetic energy for its' precession. If the loss of angular momentum of the flywheel about the rod, due to frictional forces acting on the wheel, can be neglected, then we can explain the deviation of the gyroscope's rotation axis (about it's rod) away from the z-axis (where it was initially) to balance the increase in angular momentum about the z axis due to the precession about the z axis, so that the angular momentum about the z axis would be conserved. If there were no frictional forces, the angular momentum about the z axis would be totally conserved as it is always perpendicular to the torque.